November 2023

Zettelkasten: My New Everything System

I know, I know. Did a PhD student once again get distracted by the tools to get their reading annotating, and storage of papers in order, rather than just reading and writing? The jury may forever be out on that one. In my time as a student, I have tried many, many note-taking, annotating, and storage methods and software. Many were very helpful, but none stuck with me. My ideal setup requires a few things: minimal and aesthetic design (it needs to be beautiful and sparse), contain a graph tool, optimal workflows (the tool has to work for my tasks and lend itself to repetition), and must be open-source and private.

A tall order! Well, I’ve come across something that is hitting most of those notes.

So, before I delve too deeply on the software, it’s important to outline my knowledge consumption and production methodology.

What do I need to do?

I am in my third year of my PhD and am at the point where I always have a few research projects in the pipeline. So, a literature review always needs to be knitted together to begin a paper, review comments assuaged, or contextualization in a discussion section.

I am transitioning out of reading for courses and into very targeted and narrow reading for dissertation and general publication. So, this struck me as a great time to revamp the way I: read, annotate, take notes, store those notes, reference those notes, and write academically.

My previous method was as follows:

-

- Read: Articles go to Zotero and books are physical copies. I snag a reference of the book to store on Zotero. Simple.

- Annotate: I used to try highlighting and embedding notes in those highlights, but this quickly became cumbersome as I like to read on an iPad and highlight with a stylus. The note-taking bit would require either pulling out the laptop or a keyboard for the iPad, which just sucked. So, I ended up reading, highlighting, and then summarizing some key points about the paper in the notes section on Zotero.

- Note-taking: Because of how cumbersome (fun word) the process was, I ended up not taking formal, usable notes on many papers. I also was reading a lot of papers I would never use. So many just had highlights which pointed to interesting bits.

- Writing: Well, this is where things didn’t go so well. I would try to search and if I didn’t remember the right paper, good luck sifting through the thousand papers in Zotero. Most papers only had highlights and no notes, so if I read it a year or more ago, then it was useless and I read it again. Even the notes I did have were insufficient to repurpose in writing.

Essentially, once I got to the meaningful writing stage for an actual research paper, then all of my work reading, annotating, and note-taking felt like a lot of effort with little pay out.

I can’t express how stupid this process is. It’s prescriptive and rote and boring. And it’s the same process I was told to use by grad students and faculty alike time and time again.

When thinking about a new system I wanted a few things: I want reading to serve a purpose, I want my annotations to be useful, and I want the process to feel like I am getting the idea from an article and putting it together with other related ideas. In a sentence, I want the reading/annotating process to be a part of the writing/knowledge process.

Zettelkasten

Some of you may have heard of this method, or a similar-ish one called a “memex.” Let’s go briefly over what the deal with it is.

Obligatory Historical Context

Zettelkasten was created by Niklas Luhmann, a drum roll social scientist! He is mostly famous for productivity. 50 books and 600 articles is, well, kind of wild. Luhmann popularized (I mean, it’s still obscure) the Zettelkasten method. Back in the day, this was done with notecards and slipboxes. The crux of this system is the use of hypertext. Ah! But wasn’t this before computers? Yes, yes it was, but the concept still applies. The goal is to place your knowledge into a web of thoughts rather than a nested set of notes.

The goal is to create connections across texts, rather than organize them. Let me break it down.

This is in contrast to information retrieval tools, such as Wikipedia. This divergence is because of two points. First, Wikipedia pages are not singular ideas. Second, embedded links refer to other general pages, rather than specific thoughts. So, it allows you to connect information, but not knowledge. Which is fine, it’s not for that. But, connecting knowledge is what academia is all about, and that’s what Zettelkasten is all about.

The Zettel

Core to the Zettelkasten system are the notes, or “Zettels.”

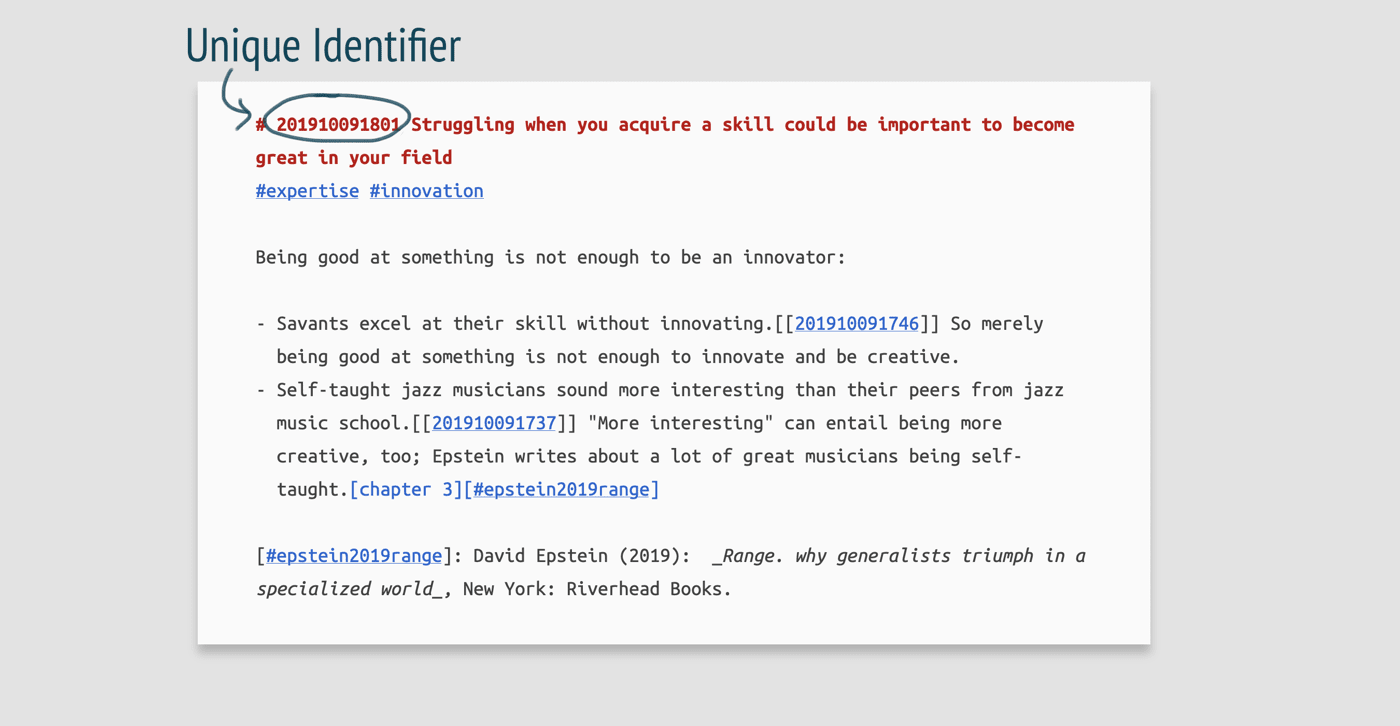

Image Source: https://zettelkasten.de/introduction/

Each Zettel contains:

-

- Unique Identifier: Just so you have a reliable, easily referenced way to tell each one apart. This can be a string of numbers and letters, or a unique sentence. If you are using software, then this will be built-in.

- Tags: In the original system there would be an index card called a “register” with tag topics and associated unique IDs. Again, with software, once you tag you can automatically filter, so no need to collate these links.

- Note: The most important idea about notes is that they need to be atomic. Irreducible. When you read a text, every time you have an idea you write it in your own words. It must be your own words and it must be one, singular idea.

- Links: An equally important component of notes are building connections. When you are writing the note and you notice a connection to another text, reference the unique ID of the second text within your note. This creates a link and allows for hypertext. This is how you will snowball into a bibliography.

- Reference: The citation of the source you are taking notes about.

So, what is the point of this? Let’s work through it.

Two of the major issues with standard note-taking is that it’s hard to disambiguate context (notes tend be summarizations rather than original creation) and they scale poorly. You go to reference an article you read a year ago and you you have to re-read to understand why you highlighted a passage or wrote a particular note. You end up repeating all of the labor annotation and highlighting were supposed to accomplish.

Zettels effectively solve this by: creating original thought, connecting those thoughts to your other thoughts, and placing them in a web rather than a tree.

Luhmann would use a manual tagging system to create topical entry points for individual ideas and references. He would capture singular, irreducible ideas (in his own words) on single notecards, create a unique ID, add a citation, a topical tag, and place them in his cabinet. You can “enter” your archive in multiple ways, such as high-level tags, individual zettles, or by inspecting a graph (if you are using software). What resulted was a web rather than a tree of ideas. Over time paper and book ideas emerged.

You can see how that would occur. While you are reading, you are actually writing multiple papers and books at the same time!

Final Word

Above, I made the claim that a traditional note taking/annotation system fails for multiple reasons. The outcome will require you to re-read articles, make sense of old highlights or notes, and still manually crawl through your archive searching for connections between texts. All of which makes the original labor of reading an article or book useless and highly memory-dependent, which will never scale.

Zettlekasten addresses these concerns. Instead of highlighting or marking reactions to a text, you instead form bespoke, individual thoughts based on the text. You embed relevant references. You plant multiple points of entry to effectively find this note. In this system, when you search for a topic, you are met with: original text that you can immediately port to your manuscript and leads to your next sources. You could have a draft lit review done in hours rather than weeks!